Book 1.—BEFORE THE CONQUEST

Chapter 3.—Chapter III.—The Anglo-Saxon Period.

Section 1.—Introduction to the Anglo-Saxon Period

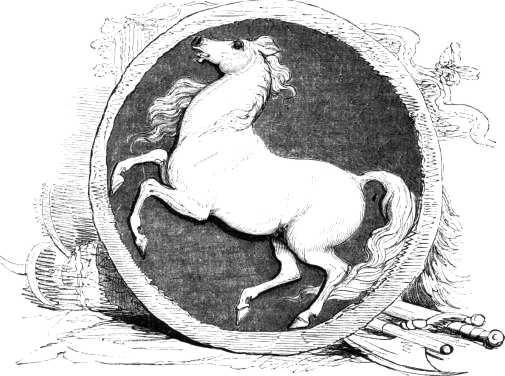

The Standard of the White Horse.

N Axe was to be laid to the

root of that prosperity which

Britain unquestionably enjoyed

under the established dominion

and protection of the Romans.

The military people whom

Cæsar led to the conquest of

Gaul were, five hundred years

afterwards, driven back upon

Italy by hordes of fierce invaders,

who swarmed wherever

plenty spread its attractions

for wandering poverty. “The blue-eyed myriads” first came to Britain as allies. The period

when they came was one of remarkable prosperity, according to the

old ecclesiastical chronicler, whose account of this revolution is the

most distinct which we possess. Bede says, that after the “Irish

Rovers” had returned home, and “the Picts” were driven to the

farthest part of the Island, through a vigorous effort of the unaided

Britons, the land “began to abound with such plenty of grain as

had never been known in any age before. With plenty, luxury

increased; and this was immediately attended with all sorts of

crimes.” Then followed a plague; and to repel the apprehended

incursions of the northern tribes, “they all agreed with their king,

Vortigern (Guorteryn),

to call over to their aid, from the parts

beyond the sea, the Saxon nation.” The standard of the White

Horse floated on the downs of Kent and Sussex; and the strange

people who bore it from the shores of the Baltic fixed it firmly in

the land, whose institutions they remodelled, whose name was

henceforth changed, whose language was merged in the tongue

which they spake. “Then the nation of the Angles, or Saxons, being

invited by the aforesaid king, arrived in Britain with three long

ships, and had a place assigned them to reside in by the same king,

in the eastern part of the island, as it were to fight for their

country, but in reality to subdue this.”

N Axe was to be laid to the

root of that prosperity which

Britain unquestionably enjoyed

under the established dominion

and protection of the Romans.

The military people whom

Cæsar led to the conquest of

Gaul were, five hundred years

afterwards, driven back upon

Italy by hordes of fierce invaders,

who swarmed wherever

plenty spread its attractions

for wandering poverty. “The blue-eyed myriads” first came to Britain as allies. The period

when they came was one of remarkable prosperity, according to the

old ecclesiastical chronicler, whose account of this revolution is the

most distinct which we possess. Bede says, that after the “Irish

Rovers” had returned home, and “the Picts” were driven to the

farthest part of the Island, through a vigorous effort of the unaided

Britons, the land “began to abound with such plenty of grain as

had never been known in any age before. With plenty, luxury

increased; and this was immediately attended with all sorts of

crimes.” Then followed a plague; and to repel the apprehended

incursions of the northern tribes, “they all agreed with their king,

Vortigern (Guorteryn),

to call over to their aid, from the parts

beyond the sea, the Saxon nation.” The standard of the White

Horse floated on the downs of Kent and Sussex; and the strange

people who bore it from the shores of the Baltic fixed it firmly in

the land, whose institutions they remodelled, whose name was

henceforth changed, whose language was merged in the tongue

which they spake. “Then the nation of the Angles, or Saxons, being

invited by the aforesaid king, arrived in Britain with three long

ships, and had a place assigned them to reside in by the same king,

in the eastern part of the island, as it were to fight for their

country, but in reality to subdue this.”

Britain was henceforth the land of the Angles—Engla-land, Engle-land, Engle-lond. Little more than a century after the settlement in, or conquest of, the country by the three nations of the Jutes, the Saxons, and the Angles, the supreme monarch, or Bretwalda, thus subscribed himself:—“Ego Ethelbertus, Rex Anglorum.” The Angles and the Saxons were distinct nations, and they subdued and retained distinct portions of the land. But even the Saxon chiefs of Wessex, when they had extended their dominion into the kingdom of the Angles, called themselves kings of Engla-land. In our own times we are accustomed to use the term Anglo-Saxons, when we speak of the wars, the institutions, the literature, and the arts of the people who for five centuries were the possessors of this our England, and have left the impress of their national character, their language, their laws, and their religion upon the race that still tread the soil which they trod.

Sir Charles Knight here quotes from a poem by Thomas Gray (1716 – 1771), The Alliance of Education and Government. A Fragment.

Say then, through ages by what fate confined

To different climes seem different souls assigned?

[. . .]

Oft o’er the trembling nations from afar

Has Scythia breathed the living cloud of war;

And, where the deluge burst, with sweepy sway

Their arms, their kings, their gods were rolled away.

As oft have issued, host impelling host,

The blue-eyed myriads from the Baltic coast.

See www.thomasgray.org for more details and the rest of the poem.

The material monuments which are left of these five centuries of struggles for supremacy within, and against invasion from without, of Paganism overthrowing the institutions of Christianized Britain by the sword, and overthrown in its turn by the more lasting power of a dominant Church—of wise government, of noble patriotism, vainly contending against a new irruption of predatory sea-kings,—these monuments are few, and of doubtful origin. The Anglo-Saxons have left their most durable traces in the institutions which still mingle with the laws under which we live,—in the literature which has their written language for its best foundation,—in the useful arts which they cultivated, and which have descended to us as our inheritance.

Their most enduring monuments are the Manuscripts and the Illuminations produced by the patient labour of their spiritual teachers, which we may yet open in our public libraries, and look upon with as deep an interest as upon the fragments of the more perishable labours of the architect and the sculptor. But of buildings, and even the ornamented fragments of churches and of palaces, this period has left us few remains, in comparison with its long duration, and the unquestionable existence of a high civilization during a considerable portion of these five centuries. But it is possible that these remains are not so few as we are taught to think. It has been the fashion to believe that the invading Dane swept away all these monuments of piety and of civil order; that whatever of high antiquity after the Romans here exists is of Norman origin. We have probably yielded somewhat too readily to this modern belief. For example, Bishop Wilfred, who lived in the seventh century, was a great builder and restorer of churches, and Richard, Prior of Hexham, who lived in the twelfth century, describes from his own observation the church which Wilfred built at Hexham. According to this minute description, it was a noble fabric, with deep foundations, with crypts and oratories, of great height, divided into three several stories or tiers, and supported by polished columns, the capitals of the columns were decorated with figures carved in stone; the body of the church was compassed about with pentices and porticoes. Such a church we should now call Norman. Within the limits of a work like ours it is impossible to discuss such matters of controversy. We here only enter a protest against the belief that all churches now existing with some of the characteristics of the church of Wilfred, must be of the period after the Conquest.

When Johnson and Boswell visited Iona, or Icolm-kill, the less imaginative traveller was disappointed:—“I must own that Icolmkill did not answer my expectations. . . . . There are only some grave-stones flat on the earth, and we could see no inscriptions. How far short was this of marble monuments, like those in Westminster Abbey, which I had imagined here!” So writes the matter-of-fact Boswell. But Johnson, whose mind was filled with the various knowledge that surrounded the barren island with great and holy associations, had thoughts which shaped themselves into sentences often quoted, but too appropriate to the objects of this work not to be quoted once more:—

“We were now treading that illustrious island which was once the luminary of the Caledonian regions, whence savage clans and roving barbarians derived the benefits of knowledge and the blessings of religion. To abstract the mind from all local emotion would be impossible if it were endeavoured, and would be foolish if it were possible. Whatever withdraws us from the power of our senses, whatever makes the past, the distant, or the future, predominate over the present, advances us in the dignity of thinking beings. Far from me, and from my friends, be such frigid philosophy as may conduct us indifferent and unmoved over any ground which has been dignified by wisdom, bravery, or virtue. That man is little to be envied whose patriotism would not gain force upon the plain of Marathon, or whose piety would not grow warmer among the ruins of Iona.”

The passage is from Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland by Samuel Johnson (1709 – 1784), and actually relates to the island of Inch Kenneth.

“The ruins of Iona” are not the ruins of “Saint Columba’s cell,” of that monastery which the old national Saint of Scotland founded in the midst of wide waters, when he came from the shores of Ireland to conquer a rude and warlike people by the power of the Gospel of peace; to preach with his followers “such works of charity and piety as they could learn from the prophetical, evangelical, and apostolical writings;” and, in addition to this first sacred duty, to be the depositaries of learning and the diffusers of knowledge. The walls amidst whose shelter Columba lived, training his followers by long years of discipline to the fit discharge of their noble office, have been swept away; the later erections are crumbling into nothingness (Figs. 198, 199); the burial-place of the Scottish kings is overgrown with rank weeds, and their tombs lie broken and defaced amidst fragments of monumental stones of the less illustrious dead. Silent and deserted is this “guardian of their bones.” The miserable hovels of a few fishermen contain the scanty population of an island which was once trodden by crowds of the noble and the learned. Here the highest in rank once came to bow before the greater eminence of exalted piety and rare knowledge. To be an inmate of the celebrated monastery of Iona was to gain a reputation through the civilized world. This was not the residence of lazy monks, as we are too much accustomed to call all monks, but of men distinguished for the purity and simplicity of their lives, and by the energy and disinterestedness of their labours. Iona sent forth her missionaries into every land from which ignorance and idolatry were to be banished by the workings of Christian love. When the bark that contained a little band of these self-devoting men went forth upon the stormy seas that beat around these western isles, to seek in distant lands the dark seats where Druidism still lingered, or the fiercer worship of Odin lifted its hoarse voice of war and desolation, then the solemn prayer went up from the sacred choir for the heavenly guidance of “those who travel by land or sea.” When the body of some great chief was embarked at Corpach, on the mainland, and the waters were dotted with the boats that crowded round the funeral bark, then the chants of the monks were heard far over the sea, like the welcome to some hospitable shore, breathing hope and holy trust. Such are the materials for the “local emotion” which is called forth by “the ruins of Iona;” and such emotion, though the actual monuments that are associated with it like these are shapeless fragments, is to be cherished in many a spot of similar sanctity, where, casting aside all minor differences of opinion, we know that the light of truth once shone there amidst surrounding darkness, and that “one bright particular star” there beamed before the dawning.

We have already quoted Bede’s interesting narrative of the arrival of Augustine in the Isle of Thanet (p. 34). The same authentic writer subsequently tells us of the lives of Augustine and his fellow-missionaries at Canterbury: “There was in the east side near the city a church dedicated to the honour of St. Martin, formerly built whilst the Romans were still in the island, wherein the queen (Bertha), who, as has been said before, was a Christian, used to pray. In this they at first began to meet, to sing, to pray, to say mass, to preach, and to baptise; till the king being converted to the faith, they had leave granted them more freely to preach, and build or repair churches in all places.” On “the east side of the city” of Canterbury still stands the church of St. Martin. Its windows belong to various periods of Gothic architecture; its external walls are patched after the barbarous fashion of modern repairs; it is deformed within by wooden boxes to separate the rich from the poor, and by ugly monumental vanities, miscalled sculpture; but the old walls are full of Roman bricks, relics, at any rate, of the older fabric where Bertha and Augustine “used to pray” (Fig. 197). Some have maintained that this is the identical Roman church which Bede describes; and tradition has been pretty constant in the belief that it is as old as the second century. Mr. King has his own theory upon the matter: “Some have supposed it to have been built by Roman Christians, of the Roman soldiery; but if that had been the case, there would surely have been found in it the regular alternate courses of Roman bricks. Instead of this, the chancel is found to be built almost entirely of Roman bricks; and the other parts with Roman bricks and other materials, irregularly intermixed. There is therefore the utmost reason to think that it was built as some imitation only of Roman structures by the rude Britons, before their workmen became so skilful in Roman architecture as they were afterwards rendered, when regularly employed by the Romans.” Whether a British, a Roman, or a Saxon church, here is a church of the highest antiquity in the island, rendered memorable by its associations with the narrative of the old ecclesiastical historian. There is a remarkable font in this church—a stone font with rude carved-work, resembling a great basin, and standing low on the floor. Such a font was adapted to the mode of baptism in the primitive times. In such a church might Augustine and his followers have sung and prayed; in such a font might Augustine have baptized. Venerated, then, be the spot upon which stands the little church of Saint Martin. It is a pleasant spot, on a gentle elevation. The lofty towers and pinnacles of the great Cathedral rise up at a little distance; the County Infirmary and the County Prison stand about it. It was from this little hill, then, that a sound went through the land which, in a few centuries, called up those glorious edifices which attest the piety and the magnificence of our forefathers; which, in our own days, has raised up institutions for the relief of the sick and the afflicted poor; but which has not yet banished those dismal abodes which frown upon us in every great city, where society labours, and labours in vain, to correct and eradicate crime by restraint and punishment. Something is still wanting to make the teaching which, more than twelve centuries ago, went forth throughout the land from this church of St. Martin, as effectual as its innate purity and truth ought to render it. The teaching has not even to this day penetrated the land. It is heard at stated seasons in consecrated places; it is spoken about in our parish schools, whence a scanty knowledge is distributed amongst a rapidly increasing youthful population, in a measure little adapted to the full and effectual banishment of ignorance. Our schools are few; our prisons are many. The work which Augustine and his followers did is still to do; but it is a work which a State that has spent eight hundred millions in war thinks may yet be postponed. The time may come, if that work be postponed too long, when the teachers of Christian knowledge may as vainly strive against the force of the antagonist principle, as the monks of Bangor strove, with prayer and anthem,

“When the heathen trumpets’ clang

Round beleaguer’d Chester rang.”

Whilst we are disputing in what way the people shall be taught, ignorance is laying aside its ordinary garb of cowardice and servility, and is putting on its natural properties of insolence and ferocity. Let us set our hand to the work which is appointed for us, before it be too late to work to a good end, if to do this work at all.

Camden describes a place upon the estuary of the Humber which, although a trivial place in modern days, is dear to every one familiar with our old ecclesiastical history: “In the Roman times, not far from its bank upon the little river Foulness, (where Wighton, a small town, but well stocked with husbandmen, now stands,) there seems to have formerly stood Delgovitia; as is probable both from the likeness and the signification of the name. For the British word Delgwe (or rather Ddelw) signifies the statues or images of the heathen gods; and in a little village not far off there stood an idol-temple, which was in very great honour even in the Saxon times, and, from the heathen gods in it, was then called God-mundingham, and now, in the same sense, Godmanham.” This is the place which witnessed the conversion to Christianity of Edwin, King of Northumbria. The whole story of this conversion, as told by Bede, is one of those episodes that we call superstitious, in which history reflects the confiding faith of popular tradition, which does not resign itself to the belief that all worldly events depend solely upon material influences. But one portion of this story has the best elements of high poetry in itself, and has therefore gained little by being versified even by Wordsworth. Edwin held a council of his wise men, to inquire their opinion of the new doctrine which was taught by the missionary Paulinus. In this council one thus addressed him: “The present life of man, O King, seems to me, in comparison of that time which is unknown to us, like to a sparrow swiftly flying through the room, well warmed with the fire made in the midst of it, wherein you sit at supper in the winter, with commanders and ministers, whilst the storms of rain and snow prevail abroad: the sparrow, I say, flying in at one door, and immediately out at another, whilst he is within is not affected with the winter storm; but after a very brief interval of what is to him fair weather and safety, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, returning from one winter to another. So this life of man appears for a moment; but of what went before, or what is to follow, we are utterly ignorant. If, therefore, this new doctrine contains something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed.” Never was a familiar image more beautifully applied; never was there a more striking picture of ancient manners—the storm without, the fire in the hall within, the king at supper with his great men around, the open doors through which the sparrow can flit. To this poetical counsellor succeeded the chief priest of the idol-worship, Coifi. He declared for the new faith, and advised that the heathen altars should be destroyed. “Who,” exclaimed the king, “shall first desecrate their altars and their temples?” The priest answered, “I; for who can more properly than myself destroy these things that I worshipped through ignorance, for an example to all others, through the wisdom given me by the true God?”

Figure spread at pages 56 and 57:

“Prompt transformation works the novel lore.

The Council closed, the priest in full career

Rides forth, an armed man, and hurls a spear

To desecrate the fane which heretofore

He served in folly. Woden falls, and Thor

Is overturned.”

The altars and images which the priest of Northumbria overthrew have left no monuments in the land. They were not built, like the Druidical temples, under the impulses of a great system of faith which, dark as it was, had its foundations in spiritual aspirations. The pagan worship which the Saxons brought to this land was chiefly cultivated under its sensual aspects. The Valhalla, or heaven of the brave, was a heaven of fighting and feasting, of full meals of boar’s flesh, and large draughts of mead. Such a future called not for solemn temples, and altars where the lowly and the weak might kneel in the belief that there was a heaven for them, as well as for the mighty in battle. The idols frowned, and the people trembled. But this worship has marked us, even to this hour, with the stamp of its authority. Our Sunday is still the Saxon Sun’s-day; our Monday the Moon’s-day; our Tuesday Tuisco’s-day; our Wednesday Woden’s-day; our Thursday Thor’s-day; our Friday Friga’s-day; our Saturday Seater’s-day. This is one of the many examples of the incidental circumstances of institutions surviving the institutions themselves—an example of itself sufficient to show the folly of legislating against established customs and modes of thought. The French republicans, with every aid from popular intoxication, could not establish their calendar for a dozen years. The Pagan Saxons have fixed their names of the week-days upon Christian England for twelve centuries, and probably for as long as England shall be a country.

Some of the material monuments of the ages after the departure of the Romans, and before the Norman conquest, are necessarily obscure in their origin and objects. It was once the custom to refer some of the remains which we now call Druidical to the period when Saxons and Danes were fighting for the possession of the land—trophies of battle and of victory. There are some monuments to which this origin is still assigned; and such an origin has been ascribed to the remarkable stone at Forres, called Sueno’s Pillar (Fig. 207). It is a block of granite twenty-five feet in height, and nearly four feet in breadth at its base. It is sculptured in the most singular manner, with representations of men and horses in military array and warlike attitudes; some holding up their shields in exultation, others joining hands in token of fidelity. There is to be seen also the fight and the massacre of the prisoners; and the whole is surmounted by something like an elephant. On the other side of this monument is a large cross, with figures of persons in authority in amicable conference. It has been held that all this represents the expulsion of some Scandinavian adventurers from Scotland, who had long infested the country about the promontory of Burghead, and refers also to a subsequent peace between Malcolm, King of Scotland, and Sueno, King of Norway. Be this as it may, the cross denotes the monument to belong to the Christian period, though its objects were anything but devotional. Not so the crosses at Sandbach, in Cheshire. These are, no doubt, works of early piety; and they are stated by Mr. Lysons to belong to a period not long subsequent to the introduction of Christianity amongst the Anglo-Saxons (Fig. 208). If so, we may regard them with no common interest; for the greater monuments of that century, after the arrival of Augustine, when Christianity was spread throughout the land, are, as far as we know and are taught to believe, almost utterly perished. Brixworth Church, in Northamptonshire, which has been so subjected to alteration upon alteration that an engraving would furnish no notion of its peculiar early features, is considered by some to have been erected in the time of the Romans. But this very ancient specimen of ecclesiastical architecture would scarcely be so interesting, even if its date were clearly proved, as the decided remains of some church or monastic buildings of the sixth or seventh centuries,—even of some building contemporary with our illustrious Alfred. There may be such, but antiquarianism is a jealous and suspicious questioner, and calls for evidence at every step. We are told by an excellent authority that “an interesting portion of the Saxon church erected by Paulinus, or Albert, [at York] has been recently brought to light beneath the choir of the present cathedral.” (Mr. Wellbeloved, in ‘Penny Cyclopædia.’) This church, founded by Edwin soon after his baptism, was undoubtedly a stone building; and it marks the progress of the arts in this century, that in 669 Bishop Wilfred glazed the windows. The glass for this purpose seems to have been imported from abroad, since the famous Benedict Biscop, Abbot of Wearmouth, is recorded as the first who brought artificers skilled in the art of making glass into this country from France. (‘Pictorial History of England,’ vol. i.)

Wilfred found the church of York in a ruinous state, on taking possession of the see. He roofed it with lead; he put glass in the place of the ancient lattice-work. Time has brought to light some relics of this church at York, buried beneath the nobler Cathedral of a later age. It is probable that the more ancient churches were as much removed and changed by the spirit of ecclesiastical improvement as by the course of civil strife. One generation repaired, amended, swept away, the work of previous generations. We have seen this process in our own times, when marble columns have been covered with plaster, and the decorated window with its gorgeous tracery replaced by a villainous casement. The Norman church builders did not so improve upon the Saxon; but it is still to be regretted that even their improvements, and those of the builders who again remodelled the Norman work, have left us so little that we can rely upon for a very high antiquity. It would be something to look upon the church at Ripon which Wilfred built of polished stone, and adorned with various columns and porticoes; or upon that at Hexham, which was proclaimed to have no equal on this side the Alps. It would be something to find some fragment of the paintings which Benedict Biscop brought from Rome to adorn his churches at Wearmouth and at Yarrow; but they perished with his library under the ravaging Danes. More than all, we should desire to look upon some fragment of that church which the good and learned Aldhelm built at Malmesbury, and whose consecration he has himself celebrated in Latin verses of considerable spirit. He was a poet too, in his vernacular tongue; and he applied his poetry and his knowledge of music to higher objects than his own gratification. The great Alfred himself entered into his note-book the following anecdote of the enlightened Abbot, which William of Malmesbury relates: “Aldhelm had observed with pain that the peasantry were become negligent in their religious duties, and that no sooner was the church service ended than they all hastened to their homes and labours, and could with difficulty be persuaded to attend to the exhortations of the preacher. He watched the occasion, and stationed himself in the character of a minstrel on the bridge over which the people had to pass, and soon collected a crowd of hearers by the beauty of his verse. When he found that he had gained possession of their’ attention, he gradually introduced, among the popular poetry which he was reciting to them, words of a more serious nature, till at length he succeeded in impressing upon their minds a truer feeling of religious devotion.” (Wright’s ‘Biographia Britannica Literaria.’) Honoured be the memory of the good Abbot of Malmesbury.

The identical bridge upon which the minstrel stood has long ago fallen into the narrow stream; the church to which the preacher invited the people by gentle words and sweet sounds has been supplanted by a nobler church, surrounded by the ruins of a gorgeous fabric of monastic splendour. We may not believe, say the antiquaries, that the wonderful porches and the intersecting arches of Malmesbury are of Saxon origin. But, in spite of the antiquaries, they must be associated with the beautiful memory of Aldhelm. His name is not now spoken in that secluded town; but the people there have still their Saxon memories of ancient days. The poor, who have extensive common-rights, say that they owe them all to King Athelstan; the humble children who learn to read in an ancient building called the Hall of St. John, connect their instruction with the memory of some great man of old, who wished that the poor should be taught and the indigent relieved,—for over the ancient porch under which they enter is recorded that a worthy burgher of Malmesbury in 1694 left ten pounds annually to instruct the poor, in addition to a like donation from King Athelstan! We wish that throughout the land there were more such living memorials of the past, even though they were the mere shadows of tradition. It is well for the lowly cottagers of Malmesbury that they are in blissful ignorance that the monument of their Saxon benefactor, in the restored choir of their Abbey Church, belongs to a later period. They look upon that recumbent effigy with reverence—they keep the annual feast of Athelstan with rejoicing. The hero-worship of Malmesbury is that of Athelstan. It has come down from the days of Saxon song when the victories of the grandson of Alfred were thus celebrated:—

Figure spread at pages 60 and 61:

“Here Athelstan King,

of earth the lord,

the giver of the bracelets of the nobles,

and his brother also,

Edmund the Ætheling,

the Elder, a lasting glory,

won by slaughter in battle

with the edges of swords

at Brunenburgh.

The wall of shields they cleaved,

They hewed the nobles’ banners.”

But Athelstan left the memory of something better than victories. He was a lawgiver; and there are traces in his additions to the Code of Alfred of a public provision for the destitute amongst his subjects. The traditions of Malmesbury have, we doubt not, a solid foundation. He was a scholar, and collected a library for his private use. Some of these books were preserved at Bath up to the period of the Reformation; two of these precious manuscripts are in the Cotton Collection in the British Museum. The Gospels upon which the Saxon Kings are held to have taken the Coronation oath is one of them (See Fac-simile of the 1st Chapter of Saint John, Fig. 226). It is not only at Malmesbury that the memory of Athelstan is to be venerated.

We have already alluded to the change of opinion which is beginning to take place with regard to the remains of Saxon architecture existing in this country (p. 54). We do not profess to discuss controverted points, which would be of slight interest to the general reader; and we shall therefore find it the safer course to describe our earliest cathedrals, and other grand ecclesiastical structures, under the Norman period. But it is now pretty generally admitted that many of our humble parish churches may be safely referred to dates before the Conquest; and some of the characteristic features of these we shall now proceed to notice. We believe, curious as this question naturally is, and especially interesting as it must be at the present day, when our ecclesiastical antiquities are become objects of such wide-spreading interest, that no systematic attempt to fix the chronology of the earliest church architecture has yet been made. In 1833 Mr. Thomas Rickman thus wrote to the Society of Antiquaries:—“I was much impressed by a conversation I had with an aged and worthy dean, who was speaking on the subject of Saxon edifices, with a full belief that they were numerous. He asked me if I had investigated those churches which existed in places where ‘Domesday-Book’ states that a church existed in King Edward’s days; and I was obliged to confess I had not paid the systematic attention I ought to have done to this point: and I now wish to call the attention of the Society to the propriety of having a list made of such edifices, that they may be carefully examined.” We are not aware that the Society has answered the call; but the course suggested by the aged and worthy dean was evidently a most rational course, and it is strange that it had been so long neglected. ‘Domesday-Book’ records what churches existed in the days of Edward the Confessor; —does any church exist in the same place now? if so, what is the character of that church? To procure answers is not a difficult labour to set about by a Society; but it is probable that it will be accomplished, if at all, by individual exertion. Mr. Rickman has himself done something considerable towards arriving at the same conclusions that a wider investigation would, we believe, fully establish. In 1834 he addressed to the Society of Antiquaries ‘Further Observations on the Ecclesiastical Architecture of France and England,’ in which the characteristics of Saxon remains are investigated with professional minuteness, with reference to buildings which the writer considers were erected before the year 1010:

“As to the masonry, there is a peculiar sort of quoining, which is used without plaster as well as with, consisting of a long stone set at the corner, and a short one lying on it, and bonding one way or both into the wall; when plaster is used, these quoins are raised to allow for the thickness of the plaster. Another peculiarity is the use occasionally of very large and heavy blocks of stone in particular parts of the work, while the rest is mostly of small stones; the use of what is called Roman bricks; and occasionally of an arch with straight sides to the upper part, instead of curves. The want of buttresses may be here noticed as being general in these edifices, an occasional use of portions with mouldings, much like Roman, and the use in windows of a sort of rude balustre. The occassional use of a rude round staircase, west of the tower, for the purpose of access to the upper floors; and at times the use of rude carvings, much more rude than the generality of Norman work, and carvings which are clear imitations of Roman work. . .

“From what I have seen, I am inclined to believe that there are many more churches which contain remains of this character, but they are very difficult to be certain about, and also likely to be confounded with common quoins, and common dressings, in counties where stone is not abundant, but where flint, rag, and rough rubble plastered over, form the great extent of walling.

“In various churches it has happened that a very plain arch between nave and chancel has been left as the only Norman feature, while both nave and chancel have been rebuilt at different times, but each leaving the chancel arch standing. I am disposed to think that some of these plain chancel arches will, on minute examination, turn out to be of this Saxon style.”

Mr. Rickman then gives a list of “twenty edifices in thirteen counties, and extending from Whittingham, in Northumberland, north, to Sompting; on the coast of Sussex, south; and from Barton on the Humber, on the coast of Lincolnshire, east, to North Burcombe, on the west.” He justly observes, “This number of churches extending over so large a space of country, and bearing a clear relation of style to each other, forms a class much too important and extensive to be referred to any anomaly or accidental deviation.” Since Mr. Rickman’s list was published many other churches have been considered to have the same “clear relation of style.” We shall therefore notice a few only of the more interesting.

The church of Earl’s Barton, in Northamptonshire, is a work of several periods of our Gothic architecture; but the tower is now universally admitted to be of Saxon construction (Fig. 209). It exhibits many of the peculiarities recognised as the characteristics of this architecture. 1st, We have the “long stone set at the corner, and a short one lying on it”—the long and short work, as it is commonly called (Fig. 201). These early churches and towers sometimes exhibit, in later portions, the more regular quoined work in remarkable contrast (Fig. 200). 2nd, The tower of Earl’s Barton presents the “sort of rude balustre, such as might be supposed to be copied by a very rough workman by remembrance of a Roman balustre” (Fig. 202). 3rd, It shows the form of the triangular arch, which, as well as the balustre, are to be seen in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. 4th, It exhibits, “projecting a few inches from the surface of the wall, and running up vertically, narrow ribs, or square-edged strips of stone, bearing, from their position, a rude similarity to pilasters.” (Bloxam’s ’Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture.’) The writer of the valuable manual we have quoted adds, “The towers of the churches of Earl’s Barton and Barnack, Northamptonshire, and of one of the churches of Barton-upon-Humber, Lincolnshire, are so covered with these narrow projecting strips of stonework, that the surface of the wall appears divided into rudely formed panels.” 5th, The west doorway of this tower of Earl’s Barton, as well as the doorway of Barnack, exhibit something like “a rude imitation of Roman mouldings in the impost and architrave.” The larger openings, such as doorways, of these early churches generally present the semicircular arch; but the smaller, such as windows, often exhibit the triangular arch (Figs. 203, 205). The semicircular arch is, however, found in the windows of some churches as well as the straight-lined, as at Sompting, in Sussex (Fig. 206). In this church the doorway has a column with a rude capital, “having much of a Roman character” (Fig. 204). A doorway remaining of the old palace at Westminster exhibits the triangular arch (Fig. 212). The windows of the same building present the circular arch, with the single zigzag moulding (Fig. 211).

Figures:

Mr. Hickman has mentioned the plain arch which is sometimes found between the chancel and nave, which he supposes to be Saxon. In some churches arches of the same character divide the nave from the aisles. Such is the case in the ancient church of St. Michael’s, St. Alban’s, of the interior of which we give an engraving (Fig. 196). The date of this church is now confidently held to be the tenth century, receiving the authority of Matthew Paris, who states that it was erected by the abbot of St. Alban’s in 948.

The church at Bosham, in Sussex, which is associated with the memory of the unfortunate Harold, is represented in the Bayeux tapestry, of which we shall hereafter have fully to speak (Fig. 216). It is now held that the tower of the church “is of that construction as to leave little doubt of its being the same that existed when the church was entered by Harold.”

It would be tedious were we to enter into any more minute description of the Anglo-Saxon Ecclesiastical remains. The subject, however, is still imperfectly investigated; and the reader will be startled by the opposite opinions that he will encounter if his inquiries conduct him to the more elaborate works which touch upon this theme. It is singular that, admitting some works to be Saxon, the proof which exists in the general resemblance of other works is not held to be satisfactory, without it is corroborated by actual date. Mr. Britton, for example, to whom every student of our national antiquities is under deep obligation, especially for having rescued their delineation from tasteless artists, to present them to our own age with every advantage of accurate drawing and exquisite engraving, thus describes the portion of Edward the Confessor’s work at Westminster which is held to be of the later Saxon age; but he admits, with the greatest reluctance, the possibility of the existence of other Saxon works, entire, which earlier antiquaries called Saxon. (‘Architectural Antiquities,’ vol. v.) The engraving, Fig. 210, illustrates Mr. Britton’s description:—

“There are considerable remains of one building yet standing, though now principally confined to vaults and cellaring, which may be justly attributed to the Saxon era, since there can be no doubt that they once formed a part of the monastic edifices of Westminster Abbey, probably the church, which was rebuilt by Edward the Confessor in the latter years of his life. These remains compose the east side of the dark and principal cloisters, and range from the college dormitory on the south to the Chapter-house on the north. The most curious part is the vaulted chamber, opening from the principal cloister, in which the standards for the trial of the Pix are kept, under the keys of the Chancellor of the Exchequer and other officers of the Crown. The vaulting is supported by plain groins and semicircular arches, which rest on a massive central column, having an abacus moulding, and a square impost capital, irregularly fluted. In their original state, these remains, which are now subdivided by several cross walls, forming store-cellars, &c., appear to have composed only one apartment, about one hundred and ten feet in length and thirty feet in breadth, the semicircular arches of which were partly sustained by a middle row of eight short and massive columns, with square capitals diversified by a difference in the sculptured ornaments. These ancient vestiges now form the basement story of the College School, and of a part of the Dean and Chapter’s Library.”

One of the most curious representations of an Anglo-Saxon Church is found in a miniature accompanying a Pontifical in the Public Library at Rouen, which gives the Order for the Dedication and Consecration of Churches. (See Fig. 215, where the engraving is inaccurately stated to be from the Cotton MS.) This miniature, which is in black outline, represents the ceremony of dedication. The bishop, not wearing the mitre, but bearing his pastoral staff, is in the act of knocking at the door of the church with this symbol of his authority. The upper group, behind the bishop, represents priests and monks; the lower group exhibits the laity, who were accustomed to assemble on such occasions with solemn rejoicing. The barrels are supposed to contain the water which was to be blessed and used in the dedication. The form of the church, and the accessaries of its architecture, are very curious. The perspective is altogether false, so that we see two sides of the building at the same time; and the proportionate size of the parts is quite disregarded, so that the door reaches almost to the roof. But the form of the towers, the cock on the steeple, the ornamental iron-work of the door, show how few essential changes have been produced in eight hundred or a thousand years. Some ascribe the date of this manuscript to the eighth century, and others to the close of the tenth century. The figures of the bishop and priest (Fig. 221) are from the same curious relic of Anglo-Saxon art; for all agree that this Pontifical is of English origin. In the ‘Archæologia,’ vol. xxv., is a very interesting description of this manuscript, in a letter from John Gage, Esq. The writer, in his introductory remarks, gives some particulars of the ancient practice of the dedication of churches:

“Gregory the Great, in his instructions to St. Augustine, bade him not destroy the Pagan temples, but the idols within them; directing the precinct to be purified with holy water, altars to be raised, and sacred relics deposited; and because the English were accustomed to indulge in feasts to their gods, the prudent Pontiff ordained the day of dedication, or the day of the nativity of the Saint in whose honour the Church should be dedicated, a festival, when the people might have an opportunity of assembling, as before, in green bowers round their favourite edifice, and enjoy something of former festivity. This was the origin of our country wakes, rush-bearings, and church ales.” When Archbishop Wilfred had built his church at Ripon, the dedication was attended by Egfrid, King of Northumbria, with his brother. Ælwin, and the great men of his kingdom. The church was dedicated, the altar consecrated, the people came and received communion; and then the Archbishop enumerated the lands with which the church was endowed. After the ceremony the King feasted the people for three days. The dedication of the church at Winchelcumbe was marked by an event which shewed that the Christian morality did not evaporate in ritual observances. Kenulf, King of Mercia, with Bishops and Ealdormen, was present, and he brought with him Eadbert, the captive King of Kent. “At the conclusion of the ceremony Kenulf led his captive to the altar, and as an act of clemency granted him his freedom.” This was a more acceptable offering than his distribution of gold and silver to priests and people. The dedication of the conventual church of Ramsey is described by the Monk of Ramsey, who gives some curious details of the architectural construction of a former church. In 969 a church had been founded by the Ealdorman Aylwin, which is recorded to have been “raised on a solid foundation, driven in by the battering-ram, and to have had two towers above the roof: the lesser was in front, at the west end; the greater, at the intersection of the four parts of the building, rested on four columns, connected together by arches carried from one to the other. In consequence, however, of a settlement in the centre tower, which threatened ruin to the rest of the building, it became necessary, shortly after the church was finished, to take clown the whole and rebuild it.” The dedication of this church was accompanied by a solemn recital of its charter of privileges. “Then, placing his right hand on a copy of the Gospels, Aylwin swore to defend the rights and privileges, as well of Ramsey, as of other neighbouring churches which were named.”

But the narrative of the circumstances attending the original foundation of this church, as related by Mr. Sharon Turner from the ‘History of the Monk of Ramsey,’ are singularly instructive as to the impulses which led the great and the humble equally to contribute to the establishment of monastic institutions. They were told that the piety of the men who had renounced the world brought blessings on the country; they were urged to found such institutions, and to labour in their erection. Thus was the Ealdorman, who founded the church of Ramsey, instructed by Bishop Oswald; and to the spiritual exhortation the powerful man was not indifferent.

“The Ealdorman replied, that he had some hereditary land surrounded with marshes, and remote from human intercourse. It was near a forest of various sorts of trees, which had several open spots of good turf, and others of fine grass for pasture. No buildings had been upon it but some sheds for his herds, who had manured the soil. They went together to view it. They found that the waters made it an island. It was so lonely, and yet had so many conveniences for subsistence and secluded devotion, that the bishop decided it to be an advisable station. Artificers were collected. The neighbourhood joined in the labour. Twelve monks came from another cloister to form the new fraternity. Their cells and a chapel were soon raised. In the next winter they provided the iron and timber, and utensils, that were wanted for a handsome church. In the spring, amid the fenny soil, a firm foundation was laid. The workmen laboured as much for devotion as for profit. Some brought the stones; others made the cement; others applied the wheel machinery that raised the stones on high; and in a reasonable time the sacred edifice with two towers appeared, on what had been before a desolate waste.” Wordsworth has made this description the foundation of one of his fine ‘Ecclesiastical Sketches:’—

“By such examples moved to unbought pains,

The people work like congregated bees;

Eager to build the quiet fortresses

Where Piety, as they believe, obtains

From Heaven a general blessing; timely rains,

Or needful sunshine; prosperous enterprise,

And peace, and equity.”

Monarchs vied with the people in what they deemed a work acceptable to heaven. Westminster Abbey was built by Edward the Confessor, by setting aside the tenth of his revenue for this holy purpose. “The devout and pious king has dedicated that place to God, both for its neighbourhood to the famous and wealthy city, and for its pleasant situation among fruitful grounds and green fields, and for the nearness of the principal river of England, which from all parts of the world conveys whatever is necessary to the adjoining city.” Camden quotes this from a contemporary historian, and adds, “Be pleased also to take the form and figure of this building out of an old manuscript: The chief aisle of the church is roofed with lofty arches of square work, the joints answering one another; but on both sides it is enclosed with a double arch of stones firmly cemented and knit together. Moreover, the cross of the church, made to encompass the middle choir of the singers, and by its double supporter on each side to bear up the lofty top of the middle tower, first rises singly with a low and strong arch, then mounts higher with several winding stairs artificially contrived, and last of all with a single wall reaches to the wooden roof, which is well covered with lead.”

The illuminated manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon period (and there are many not inferior in value and interest to the Pontifical which we have recently pointed out) furnish the most authentic materials for a knowledge of the antiquities of our early Church. It is a subject of which we cannot here attempt to give any connected view. Our notices must be essentially fragmentary. As works of art we shall have more fully to describe some of the Illuminations which are found in our public and private libraries. In connexion with our church history, it is scarcely necessary for us to do more than point attention to the spirited representation of St. Augustine (Fig. 217); to the same founder of Christianity amongst the Anglo-Saxons (Fig. 222); to the portrait of St. Dunstan (Fig. 218); and the kneeling figure of the same energetic enthusiast (Fig. 224). The group representing St. Cuthbert and King Egfrid (Fig. 219) belongs to the Norman period of art.